Woodwork

Adventures at the Edge: The Work of Peter Maynard

by Robert Smith

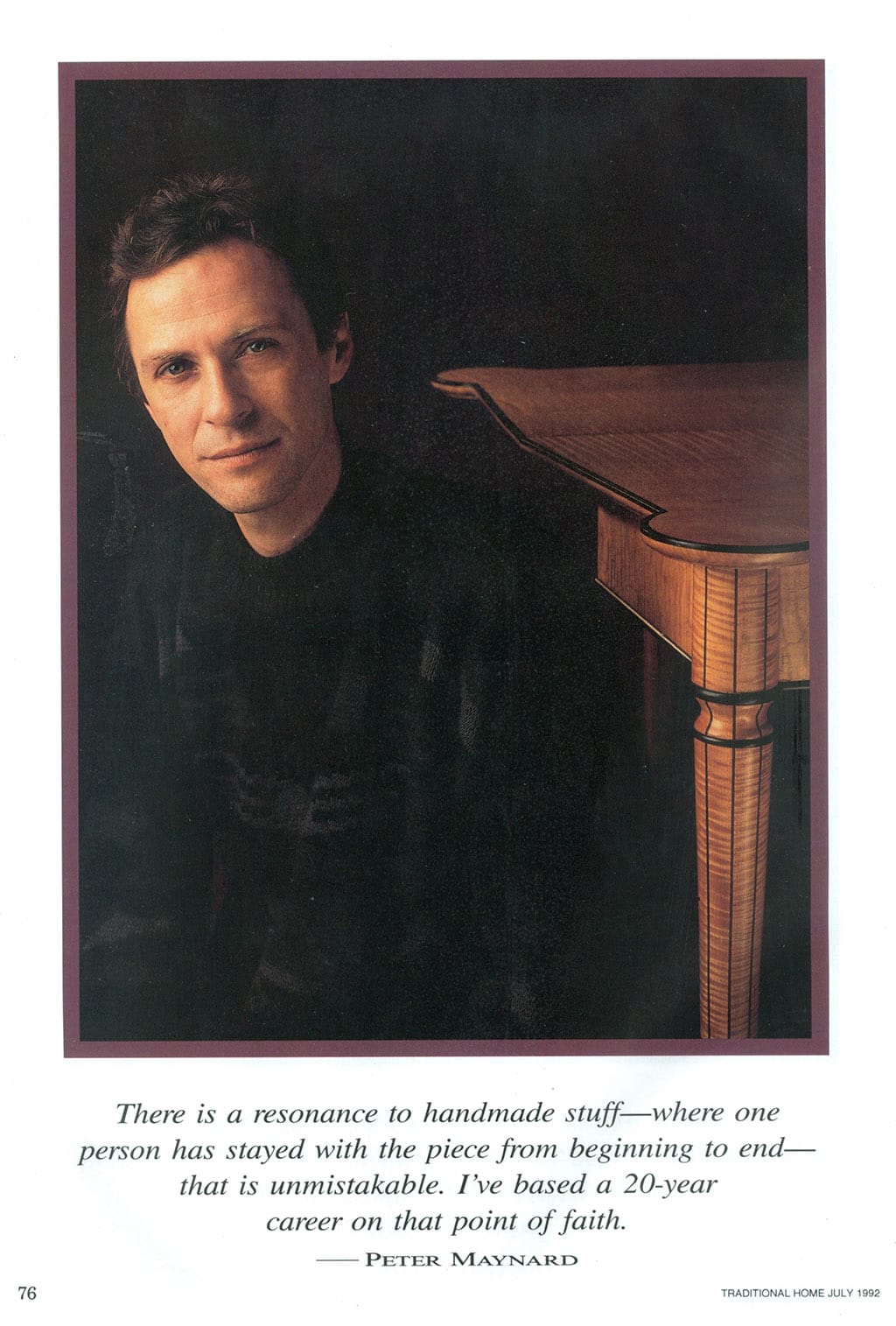

“It's like jazz,” Peter Maynard explained, describing his feelings about woodworking. “You need to be prepared to improvise. Woodworking isn't about making the same piece over and over again. There are innovations, new ideas, seeing if things work. Wood is an unpredictable material, but I like that. It sounds dramatic, but that's what happens for me everyday.”

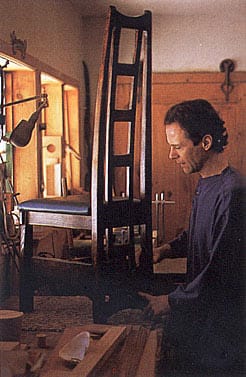

Maynard was replacing the knives on a Bridgewood long-bed jointer as we talked in his Acworth, New Hampshire shop. Caught up in his passion for woodworking, he forgot the jointer for a minute.”

That's not something a master craftsman can teach you,” he continued, gesturing with the blade in his hand to emphasize his points. “You have to learn how to give things a little time and see how they work out. You'd think that by now I'd be jaded by it, but the wood- working side of it, the learning and the innovation, that part I've not tired of. That keeps me excited.”

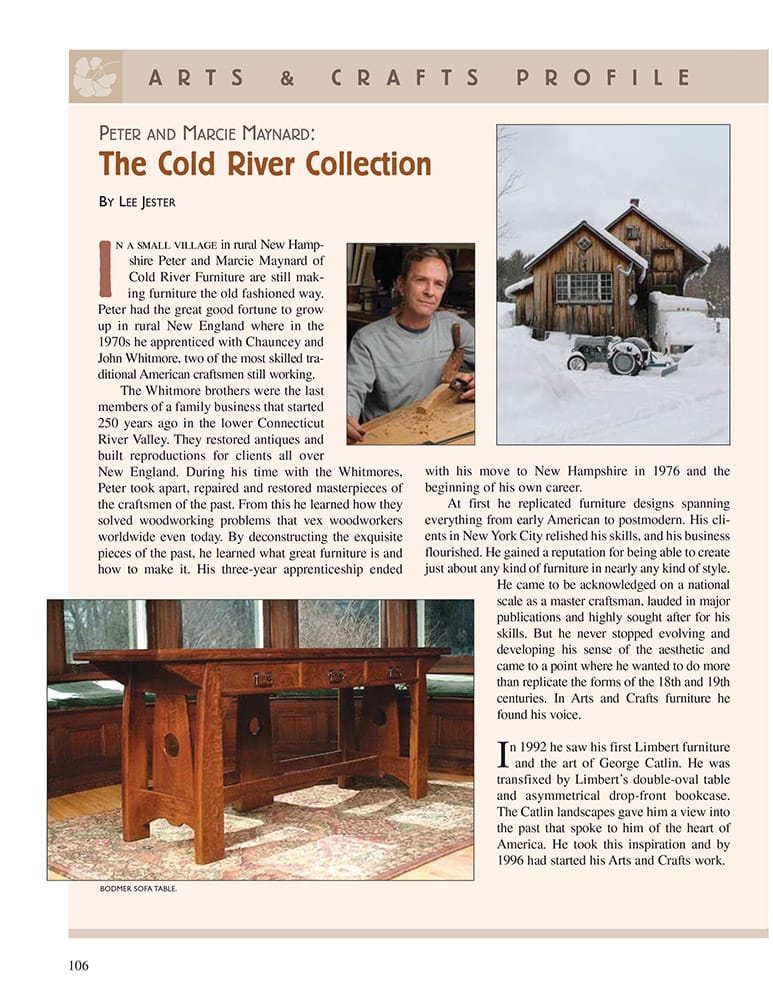

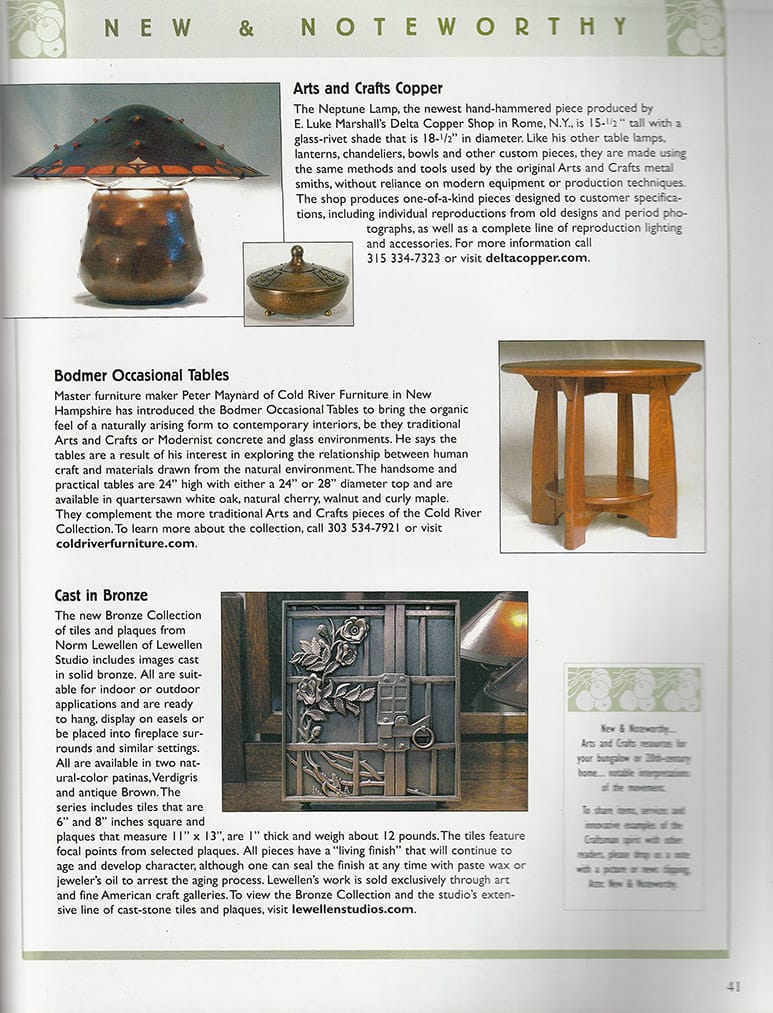

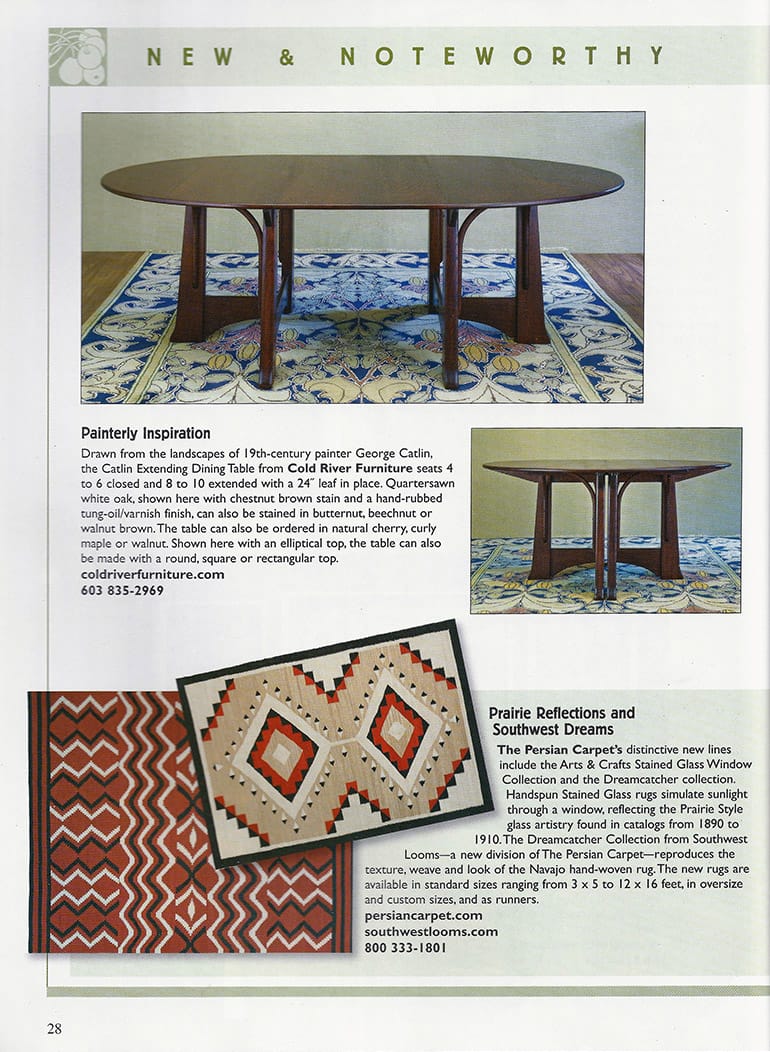

Maynard, slim, handsome, and a youthful 44, has been designing and building furniture for 25 years, most of it on his own. Even a quick look through his sizable portfolio of work—ten to a dozen major pieces every year—reveals his versatility and mastery of the craft. From the very modern, flowing design of a wave-inspired rosewood and glass tea cart to the classic lines of a mahogany English Sheraton chair, from the intricate wooden lattice on the apron of a Chinese table to the straightforward but elegant joinery of Mackintosh-style dining chairs, Peter Maynard's furniture reveals remarkable skill and a willingness to work with the whole rich history of his craft—from the ancient to the cutting edge.

For Maynard, furnituremaking isn't just about materials and techniques, it is also very much about ideas and experimentation. He draws on an in-depth knowledge of the history of his craft, combined with an ability to apply that knowledge in an intensely personal way.

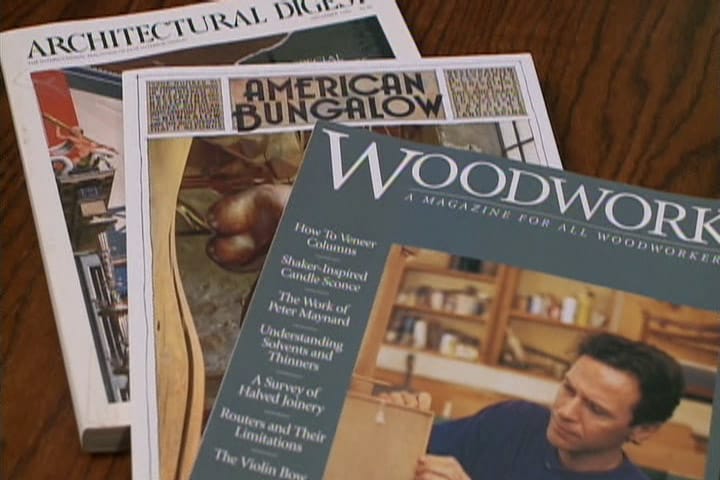

And his work is appreciated by his peers, having been featured in articles in Architectural Digest, Traditional Home, The Boston Sunday Globe, Interior Design, Colonial Homes, and Home Furniture.

To be able to design and build beautiful pieces from any period, classic to modern, is a matter of personal pride for Maynard, and the result of years studying the history of furniture design on his own. In the portfolio of work he's built over the years are examples of English Sheraton, Hepplewhite, classical Chinese, Federal, Shaker, Arts and Crafts, Art Deco, and Post-Modern pieces.

“I'm trying to specialize more now,” he said, “concentrate my work in a few areas. I would like to work only in my own styles, but in a money-driven culture it's necessary to consider all projects without bias in order to keep this somewhat 19th-century livelihood going.”

Maynard's interest in furnituremaking started at age ten when he built a stool from plans he found in a Boy's Life magazine. At fourteen he built a grandfather clock from a kit. Building these projects introduced Maynard to a hands-on world where his creative talent and intelligence blossomed.

It was working for an antique furniture restoration business, the George Whitmore Company in Middletown, Connecticut, that gave Maynard his foundation of professional woodworking skills. He began by sweeping the floors and stripping furniture, and worked his way up to woodturning and eventually building a piece of furniture. He describes the Whitmores, John and his 75-year-old father, Chauncey, as “good men, real Yankees with strong links to their local history and a willingness to pass on what they knew.” They exposed him to some of the finest antiques in New England and sparked his interest in studying period furniture.

“It was their wide-open attitude towards furniture design and construction that was really inspiring,” added Maynard. He took apart a Goddard and Townsend lowboy, then cleaned and reassembled it; this was one of the projects he credits with really teaching him how to make furniture. He worked at the Whitmore's shop for two years, and has been working on his own ever since.

“Coffee Table” (1997), combines a ship's chest mounted on a Chinese base. It measures 36x36x18 inches.

Inspired to learn all he could about the history of his craft, Maynard continued to study furniture design and went out of his way to frequent museums and other public collections of furniture. This exposure, motivated also by the diverse demands of customers, was important to Maynard in developing his own style. Arts and Crafts and Japanese furniture, as well as designers Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, are influences in what Maynard considers his signature style.

In 1975, Maynard, then 20, travelled to New Hampshire with hopes of living the craftsman's life in the country. His car promptly broke down, and he literally walked in to the remote town of South Acworth where he now makes his home. Starting with essentially no tools, he set about finding old water-powered machines and antique hand tools, and over the course of several years set up a shop and began making furniture on commission.

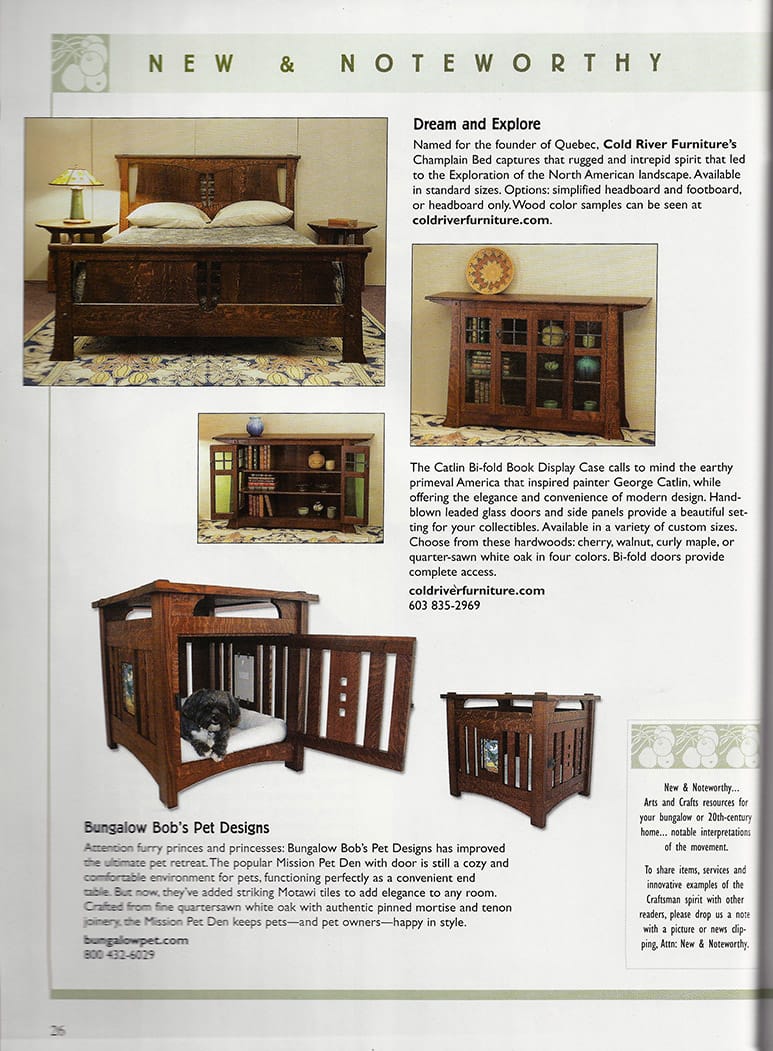

Maynard married and, with his wife Marcie, bought a house in the village, where they live today with their two daughters. During the 1970's he traveled to Europe twice, and credits the trips with helping to broaden his viewpoint, even acknowledging Stonehenge as an influence in some of his designs. But rural New Hampshire remains home.

“I love the small town life,” Maynard said. “I wish they had a little bistro on the corner, but for the most part I live fine. I love city life, but the rural setting suits me.”

In the mid-1980's, he and Marcie built an 850-square-foot shop onto the back of their house, with a full second floor loft for wood storage. The loft and a lumber shed across the road from the shop allow Maynard to buy logs locally and have them sawn to his specifications, one of the benefits of living in rural New Hampshire. In the shed he has a pile of quartersawn red oak boards, some up to 26“ wide, along with a supply of walnut, cherry, curly maple, and mahogany.

“I try to have it sawn out in matched patterns,” Maynard said. “I want to get that enhanced grain effect in my work. I've got about five thousand feet of sawn-out hardwoods. I've built a Connecticut River Valley bonnet top secretary desk all out of one large cherry log. If you want to make a cherry table top out of two book-matched 16“-wide boards, how are you going to get that unless you saw out your own lumber?”

In his home office Maynard has a large drafting table he built, and it represents a side of his business that he finds both very fulfilling and at times a little frustrating. Like many craftsmen who design and build, he knows clients often don't realize the extent of the design process. Maynard says he may at first do as many as five possible designs for a particular project, and then continue at the drafting board, perfecting the one the customer has chosen.

His broad understanding of styles helps Maynard give his clients the furniture they're looking for. One client, Emily Grant of Long Island, New York, calls him “a treasure.” “He practically furnished my new house,” Grant said. “He has an in-depth knowledge of historical design and technical design, and it was wonderful to see him take all these ideas I had in my mind and turn them into real pieces. There's a little of Peter Maynard in just about every room of my house.”

Other clients spoke highly of Maynard's ability to translate their often not-too-concrete ideas about what they wanted into furniture they love.

“His furniture is excellent and he works with you quite well,” notes Tracy Zaffino, a client from Dallas, Texas, who once had Maynard watch a movie video to get the feel for the sort of piece he wanted built.

“He takes you from a broad feeling or idea and keeps narrowing you down. He works with drawings, putting the ideas down on paper, and I'm amazed when I get them and see he's been able to capture what I want in a design.”

The whole process has given him some definite ideas about how clients should treat the craftsmen they hire. He notes, “They need to respect that that person has chosen a life of craft at the expense of making a lot of money, and needs to be supported through a challenging process.”

Peter Maynard is quick to point out that the company is called Maynard and Maynard Furnituremakers, and greatly appreciates that his wife has taken on more and more of the customer relations and sales end of the business. She has the time and patience to handle the initial developing of the client relationship, allowin her husband to focus on designing and building the furniture.

“I've got a situation that most other woodworkers wish they had,” he says, laughing. “Marcie is very affable and shows no impatience at all. There's a lot of need to build trust in this process, and the burden of trust is on us.”

Maynard's client Tracy Zaffino agrees with the need for carefully developing the client/craftsman relationship. “I just love the whole process,” Zaffino said, “but especially that moment when you get the piece shipped to you and you first get to see it. Then you realize you've got some- thing special for a lifetime.”

That's a moment Maynard also loves and looks forward to. In the world of furnituremaking-part business, part art, and by turns both fulfilling and frustrating-Peter Maynard has evolved a passionate approach to his craft that has kept it both exciting and vital for him.

Robert Smith is a freelance writer living in Bellows Falls, Vermont.